Report from Kompass - day 1

Last night was the opening night of Kompass, a small unconference-based event organised by myself and Kaspars Lielgalvis (Totaldobze Art Centre, Riga). Kompass is designed to unite Estonian and Latvian culture organisers, artists, urbanists, and activists into a networking and brainstorming event, built around the topic of 'public space'. The Kompass project has been an ongoing series of events Kaspars has been organising this year in Riga, and this time we set up a larger edition here in Tallinn, around the goal of instigating collaboration and addressing some of the common issues between the two countries.

The opening night of Kompass was the more traditional component, where we had three presentations relating to the theme. We opened the doors of Ptarmigan at 17:00 for anyone who wanted to come by early to hang out, socialise and get to know the others. This time was awkward at first, but by 20:00 the room was filled with people chattering away and the atmosphere going into the talks was quite receptive.

Teele Pehk gave the leadoff presentation. Her work with Linnalabor is amazing and I find them to be some of the most inspiring activists in Estonia. For this talk, she focused on the Kalarand project, which is not explicitly a Linnalabor venture but a more personal and organic effort that she has been central in orchestrating. Jonas Büchel from the Urban Institute in Riga followed up with a theoretical (yet accessible) discussion of urban activism, questioning some of their approaches and beliefs. Andrew Paterson, my good friend and colleague at Pixelache, closed with a look at the Camp Pixelache activities since 2010, specifically focusing on the Naissaar camp in 2013, and the approach of having a culture festival where the content is generated by the attendees.

I jotted down a lot of notes during the talks (all of which were recorded, and will be posted to the Ptarmigan podcast soon), which will hopefully serve as some starting points for today's unconference activity. This morning, I thought that it would be good to spit these ideas out here, for once actually using this blog to document something fresh in my mind.

With the Kalarand project, they've gotten somewhere by using both on-the-ground methods (of actually activating the beach) and formal procedures (registering legal challenges, negotiating with politicians, and publicising their efforts). Whether they are actually able to protect the beach, in the long-term, is unknown; the machinations of large real estate developers are impossible to predict or respond to. This made me think of what Kaspars has been dealing with in Riga - Totaldobze is temporarily located in the old Latvian Press House, and it's a property so incredibly enormous that they can't manage it themselves without a proper professional support system, so they will vacate in October. He was part of a group trying to get access to a large, abandoned area to use as a cultural centre, but the promise of "real" development won out and their efforts were futile. For those of us who are creating art and culture events, the property owners have become the new patrons - except they are few and far between, difficult to contact, and even more difficult to convince of the validity of our efforts. In Teele's case it's obvious what the benefits have been - a very popular urban beach that is used by a wide swath of the Estonian public. With activities such as Totaldobze and Ptarmigan, it's sometimes less obvious to those who have a more traditional understanding of art and culture.

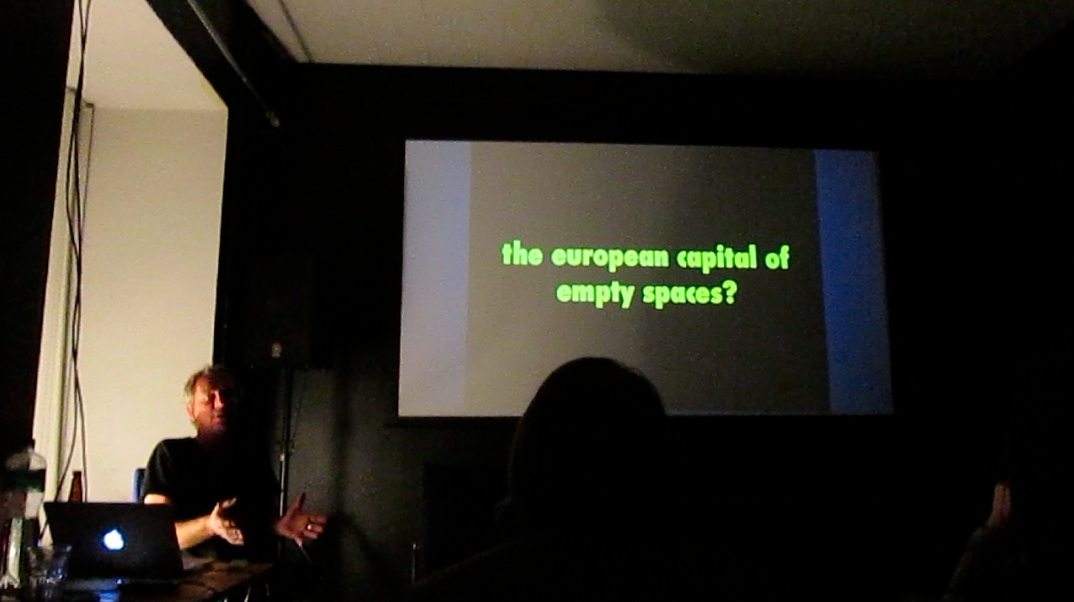

The irony of these Baltic cities is that there's a tremendous amount of empty property, usually privately owned if not completely abandoned, but rarely anything cultural happening in these spaces because of apathy and the lack of imagination. And the apathy is not exclusive to the property owners; we often fail to push for better space, more rights, and more access. This problem is happening everywhere with culture organisers, as 'space' becomes more precious in cities, and activities that don't generate obvious economic growth must struggle to compete, or rebrand themselves as 'creative industry'.

We are so often building our activities around the idea of 'temporary'; 'pop-up' has become one of the most overused words in my scene (along with 'open', ha ha), and project-based culture funding systems force us into this situation. It's all a matter of how you frame it; floating, nomadic culture projects can be dynamic and exciting, but they also end up reinventing the wheel often. I wonder if we aren't vicitmising ourselves through this strategy. Would it be better to fight for less, but for something more permanent?

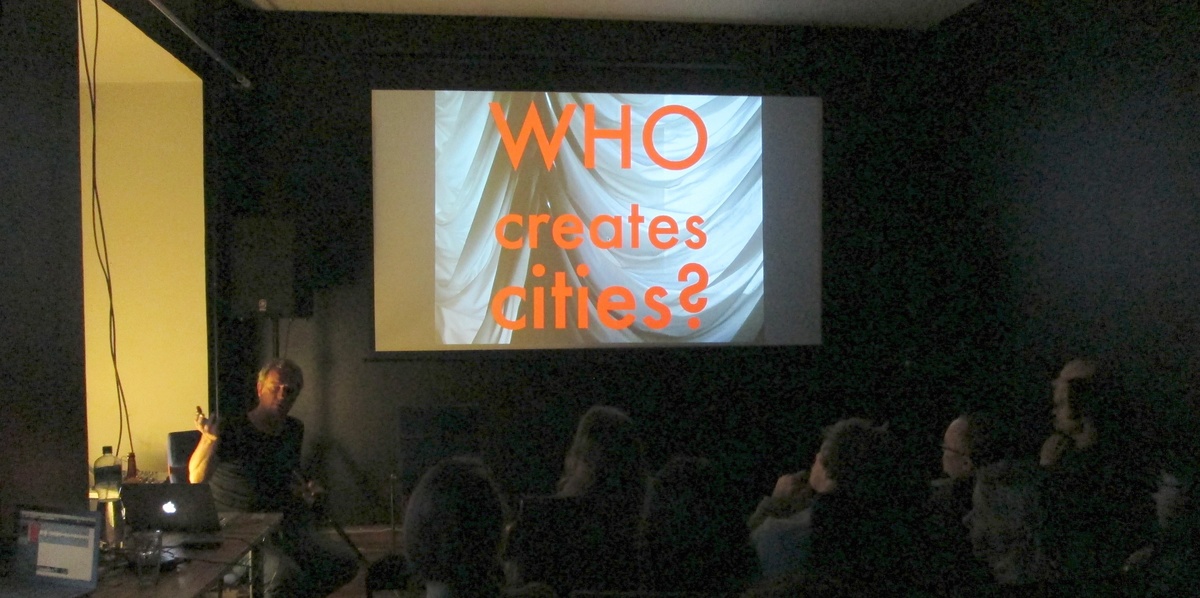

Jonas's presentation had a lot to say about the nature of people and initiatives. He asked who creates cities, and who performs in them, illustrating the idea of urban performance with examples of children. This served to build an exciting model of a city - one the celebrates curiosity, unpredictability and diversity. As I'm personally going to be changing not only my city once again, but also my activities (to a certain extent), it made me think that this creator/performer dichotomy is perhaps reductive. What about just living? Can we get back to the idea of cities as a place where people live, and find vitality and thrills in that?

Before the talks started, there was a discussion of the word 'activist' and our own personal relationship to it. I've never particularly liked that term, or considered myself anywhere close to that. But the root word 'active' is of course an important one. The point of Kompass is to build connections between people that might lead to change. Defining what that change is (or could be) is less obvious. I'm not always sure I want change (please reference Elliott Gould's brilliant monologue in the 1971 film Little Murders: you should never challenge a system unless you are completely at peace with the fact that it won't be around anymore if you succeed). Maybe I really want a form of neutrality, though I guess that is change. To resist the rhythms, pressure and pace of a city; to leave the least impact on your physical surroundings; to enrich oneself with connections, friendships and collaborations of a human nature.

Jonas also had some photos of an empty space outside of Tartu, Estonia, shot from 4 different viewpoints. They showed the supposed "wasteland" of a post-industrial landscape, with the typical forgotten post-Soviet architecture, and a homeless man living in a tent (who was presented as the most successful user of that space). The word 'wasteland' bothers me somewhat, as it really should be 'wasted land' in most contexts, unless it actually refers to a garbage dump or something. Often, these liminal places are the most beautiful and inspiring. It takes me back to my postgraduate course in Glasgow, and the discussions we had about non-space and postmodern space (built around J.G. Ballard's fiction and some of Lefebvre's theories). The real waste to me is when said beautiful and inspiring areas get a new shopping centre or unnecessary apartment complex grafted onto them. This is not a radical observation in any way, but Jonas phrased it in the language of 'space creators' and 'space experts', positing that the homeless man was occupying both roles in a more successful manner than many real estate developers (or even cultural activists).

Andrew's presentation about Camp Pixelache was not news to me (as I have participated in four out of the five camps) but served as a nice bridge into today's activities, which are modeled very much after the Camps. The different locations we have used for the camps (remote islands, less remote islands, buildings in the city centre, buildings in a nearby small city) have changed as we have continually tweaked the event to find what works and what doesn't. The most unique aspect of unconferences is in many ways the least big deal - that the people who come create the content, and as organisers we only have to provide a wire-frame for structure. Most people have plenty of ideas; it's just a matter of creating comfortable, inviting environments to support them.

Maybe that's where we failed with Kompass. I had dreamt of 30 to 40 people; we had about 16 last night and will likely only have 12 or so today. This is my problem; getting local people interested in the activities here has been near-impossible, and it almost seems like the more valuable I think the project is (for example, the Avatud Toimingud series of talks this summer) the less people show up. I'm hoping that the smaller group will create a more intimate environment and we can really have some stimulating discussions (and most importantly, outcomes) but we'll see how it goes. It's not necessarily about numbers, but the intent of the people, and I think we have a good group. But when you are talking about public space and cultural initiatives, you don't gain anything by being marginal.

The images above this post are from the presentations by Jonas and Andrew, and of the room last night, taken by Kevin Josse.